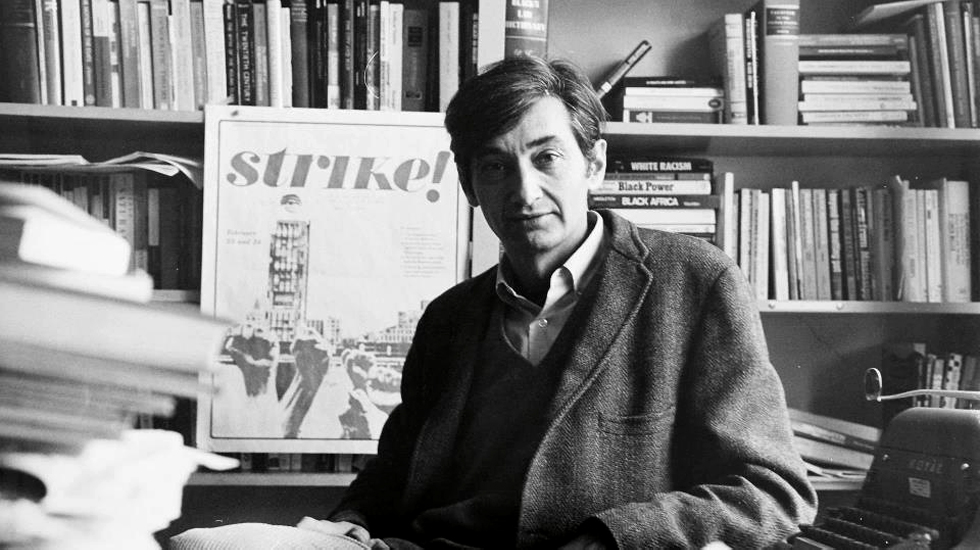

I personally think Howard Zinn is a legend. As far I remembered, the first time I heard of his name is from my younger brother, who studied in Canada and shared his reading on him. But, back then I am not yet interested in his work. As I read many of Chomsky’s books, I get interested in the idea of American Exceptionalism, this is when eventually I discovered Zinn’s lectures over Youtube. His explanation, as always, very clear and simple to understand, he does not shy to said something for what it is, he does not hide important aspect in history behind any euphemism. I literally watch almost all his lecture in Youtube, from his speech in Google, C-span, all the way through his interview with Democracy Now. Ironically, I first found this book in Lincoln’s Corner inside Georgetown’s public library in Penang. After finishing the first chapter, I decided to return the book and get myself a copy.

Howard Zinn served in the US army in WWII, he recalled his experience in bombardment campaign, dropping bombs in small villages in France. He later continues his study in history (minor in political science) and was awarded a PhD. He then was employed by Spelman College where he gets involved in the civil right movement. He also played significant role in anti-war movement to oppose US military campaign in Vietnam and Iraq.

A People’s History of The United States was his most famous and influential book. It was first published in 1980 and quickly gained traction, millions were sold out, and reprinted. In the book, Zinn collected accounts and speeches of people who were disfranchised, massacred, and crushed. He seek to re-tell history not from a victor’s point of view, but from the perspective of the red Indians, black slaves, poor farmers, ordinary soldiers and workers. He wrote:

“My viewpoint, in telling the history of the United States, is different: that we must not accept the memory of states as our own. Nations are not communities and never have been. The history of any country, presented as the history of a family, conceals fierce conflict of interest between conquerors and conquered…” (pg. 10)

The book starts with the story of the Arawaks, a tribe who welcome Columbus and his company on their mission to search for gold. Zinn wrote on how the Indians were mistreated, captured and shipped to Europe as slaves, enslaved to mine and work in plantations. As the European came in, they were systematically depopulated. As years passed by, and during the Revolutionary years of the 1760s, the wealthy elite have three main concerns. One is the Indian hostility, second is the black slaves revolts and third was the angry propertyless poor whites. If ever these despised groups combined, the power of the ruling elites would be shaken.

Many Americans during the Revolutionary war were reluctant to fight. Neutral people are forces to duty while the very rich can buy their way out to avoid conscription. The ruling elites understand that war help them navigate through internal trouble, and gave them a more stable and secure position. It was the poor who did much of the actual fighting, during 1775 and 1783 they are the one who suffer the most.

Zinn also noted on how Washington’s first administration, ally them self with the rich, passed tariff to help manufacturers, agreed to pay the war bond holders, and passed law on tax to raise money for tax redemption. Talking on the Founding Fathers, Zinn wrote:

“They certainly did not want an equal balance between slaves and masters, propertyless and property holders, Indians and white.” (pg. 101)

Zinn also recounted speeches from Frederick Douglass when exploring the subject of slavery in 1857. Douglass note that there are no progress without struggle, and if the black slaves want to set themselve free, they should all embrace the struggle, either morally or physically. The later continue that there will be no progress without struggle, he then said “They want rain without thunder and lightning’.

It was thought that Abraham Lincoln fight the American Civil War against the confederate’s forces, as a moral fight to abolish slavery. Zinn debunked this myth, the move to emancipate black slave was a military move to win the war. He recalled one of Lincoln letter where he wrote to Horace Greeley “My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or destroy Slavery.” (pg. 191)

There are still traces of exploitation even after slavery has been abolished. This new kind of exploitation is very much disguised, it was branded with a fancy name ‘free market’ and ‘free enterprise’. The maldistribution of wealth is concealed, and protected by law, which make it look fair on the outside. The use of law to protect the rich leads to civil unrest, labor strikes and riot. In 1872 working people formed National Labor Union, went on strike and won the eight-hour day. Throughout the book, Zinn portrayed the American history as the history of the working people, fighting for their rights.

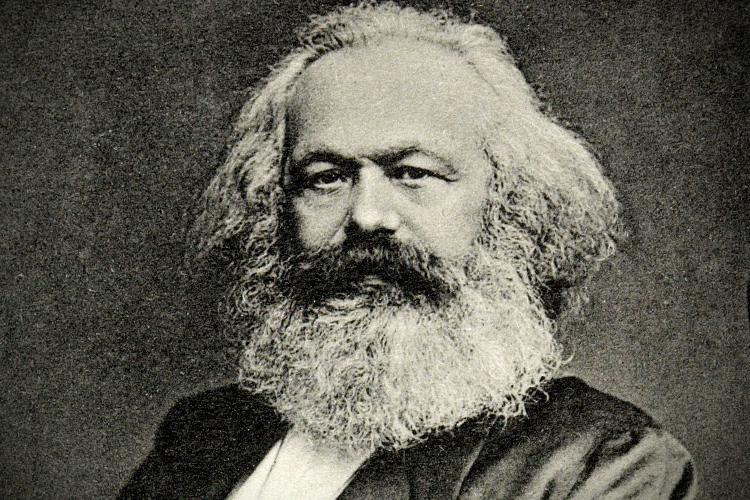

Government behavior resembled what Karl Marx has described, as a capitalist state. The government “pretending neutrality, serving the interest of the rich, settle upper-class disputes peacefully, control lower class rebellion and adopt policies that provide long-range stability to the system.” (pg. 258). The policies will never undergo any important change, be it Republican or Democrat who wins the election. Zinn also elaborate on how corporation made donation to both party, in which whoever wins, they have their say in the policies.

On the reason America went on war with Japan, Zinn disputed that Roosevelt was telling the truth. Roosevelt, Zinn said ‘lied to the public’ and misstated the facts. This is an important lesson Zinn always talk throughout many of his lectures, that the presidents have been lying in the history, and when president rush the public into war, it is important for the public to take a step back and analyze the evidence. He also criticized US involvement in El Salvador and put a spotlight to the massacre of civilians in El Mozote by soldiers trained by the US.

In his critics to the Reagan’s policy to cut funding for children, he quoted Marian Wright Edelman from Children’s Defense Fund. She said “our misguided national and world choices are literally killing children daily” (pg. 610).

My favorite chapter of the book is ‘The coming revolt of the guards’ where Zinn sum up many of his perspectives, giving a glimpse of the solution and gave us the hope for change. He discussed about how the ordinary working people are the guardian of the current system, and if they are awaken, if they suddenly believe that what they are doing is morally wrong, and if they stop working, the system will fall apart. The power, according to Zinn, rest on the people.

When discussed about the state of economy, Zinn’s offer another perspective. When the government spending to maintain military machine constantly high, when the trade multiplied, the top corporation recorded an increase in profit, but the wages of people are in steady decline, can we said that the economy is healthy? His answer, depend on which group of people you are referring to.

Zinn constantly questioned the need of war and the abandonment of diplomacy. Asking hard question whether the lucrative commercial gain in supporting undemocratic tyrant abroad justify the human cost suffer by the population. He examines several of US unilateral intervention, and emphasized on the non-military option which can solve the conflict at the same time saving the innocent lives in the process. He called for ‘non-militant’ solution for the world problems.

Through his writing I felt that the ideal world to live in is not beyond reach. A reasonable way to govern a nation is not something so utopian, it is within reach if we are bold enough to make some radical changes. In the afterword, Zinn envisaged a thinking to wiped out national boundaries in our thought. This will made our decision much clearer, and we will no longer see the need for war, for war is always against the children. In the absent of national boundaries, Zinn said “indeed our children” (pg. 685)

Redefining patriotism – is one of the important contributions of this book. I felt that this review is incomplete without a quote from Eugene Debs which he said “They tell us that we live in a great free republic, that our institutions are democratic, that we are free and self-governing people. That is too much, even for a joke. Wars throughout history have been waged for conquest and plunder. And that is war in a nutshell. The master class has always declared the wars, the subject class has always fought the battles.” It is not unpatriotic to denounce war, as Noam Chomsky has suggested when questioned how to end terrorism, he said “stop participate in one”.

Author of several books including Berfikir Tentang Pemikiran (2018), Lalang di Lautan Ideologi (2022), Dua Sayap Ilmu (2023), Resistance Sudah Berbunga (2024), Intelektual Yang Membosankan (2024), Homo Historikus (2024), DemokRasisma (2025), dan Dari Orientalisma Hingga ke Genosida (2025). Fathi write from his home at Sungai Petani, Kedah. He like to read, write and sleep.

THE ORIGINAL BLACK ELITE

THE ORIGINAL BLACK ELITE