THE NEW BROOKLYN

What It Takes to Bring a City Back

By Kay S. Hymowitz

199 pp. Rowman & Littlefield. $27.

Words are always shifting in their meanings, but what has happened to the word “gentrification” is something of a special case. Not too long ago, it was pretty much a value-neutral term for the process by which communities exchange one set of residents for another. Now it is a term of opprobrium, a word that conjures up the cruel displacement of defenseless poor people by a greedy and arrogant professional elite.

There is a whiff of hypocrisy in all this, or at least a strong element of disingenuousness. Ask mayors what they wish for in their city centers, and they will give you similar answers — safe streets, bustling sidewalks, busy stores and restaurants, and a healthy and growing residential population with plenty of money in its pocket. Mayors and city planners spend much of their time maneuvering to create these things, but with one inevitable disclaimer: They don’t want it to lead to gentrification. What they choose not to admit is that the change they are seeking and the change they claim to fear are exactly the same thing.

As “gentrification” has become an increasingly dirty word, the volume of disingenuous posturing on the subject has increased dramatically, and the supply of balanced reporting has declined. One writer who has managed to speak sensibly above the din is Kay S. Hymowitz, a contributing editor at City Journal and a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute. “The New Brooklyn” is her admirably clearheaded assessment of the borough that sometimes seems the epicenter of American gentrification.

Brooklyn’s overall return to affluence in the 21st century has been a remarkable event, and it is one that Hymowitz describes with an unmistakable relish. “A left-for-dead city marinated in more than a century of industrial soot,” she writes, “became just about the coolest place on earth and the paragon of the postindustrial creative city.” But the core of the book is the portrait that she draws of half a dozen individual neighborhoods, and the subtleties that each of them reveals about the gentrification process.

Writing of now fashionable Park Slope, where Hymowitz herself lives, she makes some provocative sociological points that tend to get lost in the larger commotion. One is that class is now far more important than race: White gentrifiers with elite-school credentials and well-paying jobs get on famously with their well-educated black counterparts. The people they fail to connect with are their white working-class neighbors, most of whom were there before gentrification and have never been comfortable with it.

In a similar way, work and avocation are more important than geography. The relationships that matter most in Park Slope are those that link residents who share professional and leisure-time interests, not those of people who happen to live next door to one another. The days when neighbors bonded during long summer evenings on the front stoop are a distant memory. Today’s Park Slope citizens are oriented toward their backyard gardens and cedar decks; they may not know the family next door at all.

Park Slope is a neighborhood of elegant but formerly dilapidated brownstones now restored to its 19th-century glory. Nearby Williamsburg is something else entirely: an old working-class enclave whose industrial grittiness became pretentiously chic in ways that no one thought possible. In Williamsburg, the artists who arrived as pioneers in the 1980s resent the techies who showed up in the early 2000s, and both resent the Wall Street traders who moved in after them. All three groups are scornful of the huge condo towers that have sprung up on the Williamsburg waterfront as a result of rezoning in the past decade and, as Hymowitz puts it, erected a “massive wall between the community and the waterfront park.” Those towers are a dark side of gentrification, and Hymowitz candidly portrays them as such.

The way for any collection of neighborhood profiles to succeed is to make fine distinctions between places that casual observers tend to consider similar. Hymowitz does that effectively in the case of Bedford-Stuyvesant and Brownsville, two neighborhoods widely perceived as outposts of African-American poverty and social dysfunction. Bedford-Stuyvesant hit bottom in the 1960s and 1970s, but more recently its architectural graces have made it attractive to middle-class newcomers, many of them black professionals. Brownsville, on the other hand, is an early-20th-century Jewish tenement slum that became an isolated fortress of public housing, a “dumping ground for the most welfare-dependent and least capable of Brooklyn’s black poor.” Gentrification has not touched it — at least not yet.

It is in discussing Brownsville that Hymowitz reveals her ultimate conclusions about the subject of her book. She challenges the local activists there who have voiced their opposition to the coming of the white middle class. “They’re making a mistake,” Hymowitz writes. “The difficult truth — and it is immensely difficult — is that gentrification would be about the best thing that could ever happen to Brownsville.”

And indeed, the thesis that emerges from the book, balanced as the author tries to make it, is that gentrification has been, on the whole, a good thing for Brooklyn. No fair-minded observer can deny, and Hymowitz does not try to deny, that significant numbers of poor people have been forced to leave Park Slope and Williamsburg, that this is happening in Bedford-Stuyvesant and that it will happen in more remote parts of the borough in the years to come.

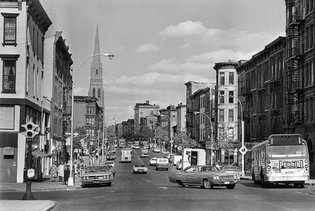

And yet when one considers Brooklyn as much of it stood 40 years ago — once-vibrant communities whose residential blocks had become unsafe by day and by night; elegant brownstone homes that had fallen into dangerous disrepair; commercial districts with storefronts abandoned by merchants who could no longer make a living from them; job losses mounting in every corner of the borough — when one thinks back to those depressing days, and compares them with the Brooklyn of 2017, the ultimate logic of Hymowitz’s argument is compelling: Gentrification has winners and losers. Urban decline makes losers out of everyone.

Related Posts

Kami mengalu-alukan cadangan atau komen dari pembaca. Sekiranya anda punya artikel atau pandangan balas yang berbeza, kami juga mengalu-alukan tulisan anda bagi tujuan publikasi.

Leave a Reply