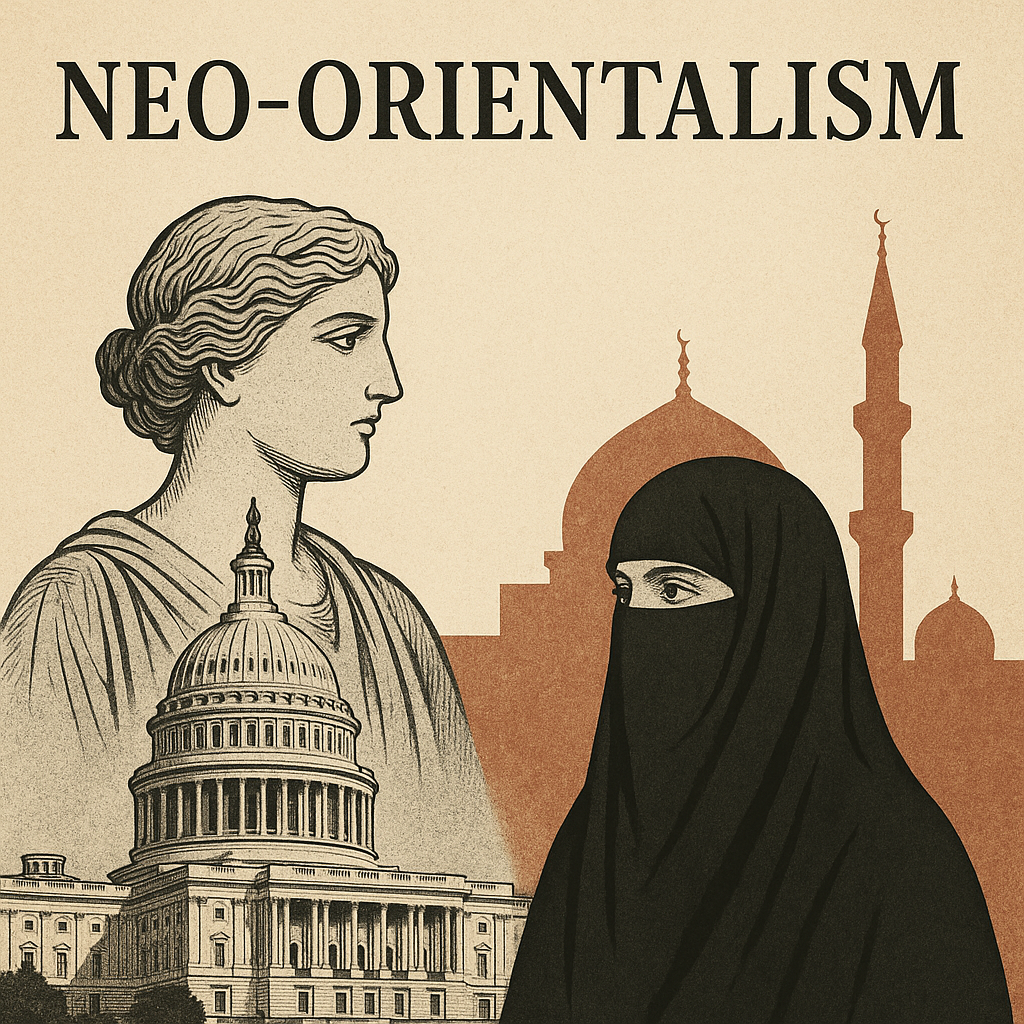

Since the publication of Edward Said’s seminal work Orientalism (1978), the concept of Orientalism has remained central in discussions about the West’s representations of the East. Orientalism refers to the constructed, often patronising depiction of Eastern societies as static, exotic, backward, and inferior to the rational, progressive West. However, with the evolution of global power dynamics, especially in the post-Cold War and post-9/11 era, a reconfiguration of these orientalist frameworks has emerged. This development is often referred to as neo-Orientalism. This essay explores the nature, characteristics, and implications of neo-Orientalism, highlighting how it differs from classical Orientalism and how it continues to shape Western knowledge, policy, and culture in the 21st century.

Defining Neo-Orientalism

Neo-Orientalism refers to the contemporary reproduction of orientalist narratives in a new geopolitical and media landscape. While classical Orientalism operated largely through colonial discourses and academic institutions, neo-Orientalism finds expression in mass media, pop culture, think tanks, humanitarian discourse, and global security paradigms. It continues to essentialise the East—particularly the Islamic world—but often under the guise of liberal values such as democracy, women’s rights, secularism, and human rights.

Importantly, neo-Orientalism is not merely a repetition of older tropes; it adapts to contemporary anxieties and global shifts. After the fall of the Soviet Union, Islam replaced communism as the West’s primary ideological “Other”. The events of 9/11 and the subsequent “War on Terror” further intensified neo-orientalist narratives, casting Muslim societies as inherently violent, irrational, and in need of Western intervention or reform.

Key Features of Neo-Orientalism

- Secular-Liberal Framing: Neo-Orientalist discourses are often couched in the language of liberalism. Instead of overt colonial rhetoric, they promote a “civilising mission” through democracy promotion, gender rights, and liberal education. For example, the occupation of Afghanistan was frequently justified in Western media as a campaign to liberate Afghan women, ignoring the broader context of foreign occupation and local agency.

- Internalisation by Native Informants: One of the striking features of neo-Orientalism is its reliance on native voices who confirm Western views about their own societies. These “native informants”—intellectuals, activists, or exiles—are often celebrated for criticising their home cultures but rarely afforded space to critique Western imperialism. This strategy lends legitimacy to neo-orientalist narratives and obscures the power imbalance in the production of knowledge.

- Hyper-visibility of Islam: While classical Orientalism focused on a broader range of Asian and Middle Eastern cultures, neo-Orientalism is primarily concerned with Islam and Muslims. Muslims are scrutinised as potential threats, whether through discourses on terrorism, Sharia law, or the “clash of civilisations”. This often manifests in securitisation, surveillance, and policies targeting Muslim populations, both abroad and within Western societies.

- Technological and Cultural Domination: Neo-Orientalism is disseminated through globalised media—Hollywood, news outlets, streaming platforms, and social media—which shape public perceptions. Films and TV shows often depict Muslim-majority countries as dangerous, chaotic, or oppressive, while Western characters play the role of saviours or reformers.

Differences from Classical Orientalism

Whereas classical Orientalism was a product of colonialism and imperial conquest, neo-Orientalism operates in a post-colonial and often neoliberal context. It no longer requires direct rule to assert cultural dominance; rather, it thrives on soft power, discursive control, and economic influence. Furthermore, while classical Orientalism often portrayed the East as alluring and mysterious, neo-Orientalism frequently depicts it as threatening and in need of containment or transformation.

Implications and Critiques

The persistence of neo-Orientalism has serious implications for international relations, immigration policy, and inter-cultural dialogue. It reinforces stereotypes, justifies foreign interventions, and stifles genuine engagement with non-Western epistemologies. Moreover, it impedes efforts to build solidarities across global communities by framing the East/West divide as ontological rather than political.

Critics of neo-Orientalism argue that it masks Western hegemony behind a veneer of liberal concern. For instance, Lila Abu-Lughod questions whether the language of “saving Muslim women” serves more to satisfy Western self-image than to empower the women themselves. Similarly, Hamid Dabashi critiques the role of native informants in sustaining empire through culturally coded compliance.

Conclusion

Neo-Orientalism is a subtle yet pervasive force in today’s global order. While it differs in form and context from its classical predecessor, its core function remains: to maintain a hierarchy between the West and the non-West through representational power. Understanding and challenging neo-Orientalism is essential not only for deconstructing harmful stereotypes but also for envisioning a more equitable and pluralistic global discourse. It requires a critical awareness of how knowledge is produced, who produces it, and in whose interest it circulates.

Related Posts

Kami mengalu-alukan cadangan atau komen dari pembaca. Sekiranya anda punya artikel atau pandangan balas yang berbeza, kami juga mengalu-alukan tulisan anda bagi tujuan publikasi.