The observation that “writing about music is like dancing about architecture” has been attributed to everyone from Martin Mull to Frank Zappa to Thelonious Monk. It’s famous enough that it’s almost hackneyed by now, yet it’s as good a description as any for the nearly impossible task of using words to describe the sacredly wordless. Get bogged down in technical terms like diatonic interval and chromatic diesis and you risk sounding gratingly wonkish. Indulge in platitudes like “lyrical melody” and “haunting chords” and you’re a pathetic lightweight, a philistine.

So you’ve got to hand it to musicians who put down their instruments long enough to write entire books. Classical musicians, especially, carry a set of burdens that can make cross-genre endeavors uniquely challenging. They are confined to practice rooms for hours, days and years on end and tyrannized by necessary perfectionism; their achievements in many ways rest on their ability to shut out the noise of the outside world and play the same set of notes again and again. And while that can yield fine results, it doesn’t always lend itself to the kind of divine hubris required to put your thoughts in print and expect anyone to care enough to read them.

In a memoir published last year and two forthcoming this month, an oboist, a concert pianist and a guitarist set out to map the intersections of their musical lives and the much thornier vagaries of life in general. For Marcia Butler, the oboe was a protective garment and a ticket to the world, though both applications came at a steep price. As an awkward, antisocial preadolescent in 1960s Long Island, Butler is coerced into “a binding and sickening pact” with her father; if she confers sexual arousal by sitting on his lap, he will drive her to oboe lessons. “My father was my epic Wagnerian Wotan,” Butler writes in THE SKIN ABOVE MY KNEE: A Memoir (Little, Brown, $27), referring to Richard Wagner’s ruthless patriarch. “I was his dutiful daughter Brünnhilde.”

Butler wins a scholarship to the Mannes College of Music, where she undergoes the perfunctory comeuppances of high-level music study, including an assignment to go back to the basics and practice nothing but long tones for three mind-numbing months. Long tones are notes held until you run out of breath, and anyone who’s ever seriously studied a wind instrument (I played the oboe with varying degrees of resolve from childhood through college) will experience traumatic flashbacks reading about Butler’s stages of grief around this situation. “The time spent crying could be used for playing the long tones,” she writes. “You do as you’re told.”

Outside the conservatory, it’s 1970s New York City, and Butler by default embarks on the hero’s journey particular to that time and place, stealing food and spare change from a roommate, riding the subway with fake tokens and sleeping with an assortment of grungy ne’er-do-wells, including one who winds up at Rikers Island for what Butler later learns was a rape at gunpoint. In one especially affecting scene, Butler plays a Harlem church gig and is discreetly acknowledged by a congregant who recognizes her from the bus to Rikers.

“That was the thing about being a girl who played the oboe and had a boyfriend in the clink,” Butler explains, in what is surely the only time such a sentence has ever been committed to paper. “It was easy for me to separate the two realities and carry on as if all were harmoniously blended.”

If the colluding forces of her father’s abuse, her relentless self-discipline, and her love of opera and similarly concupiscent classical works split Butler into two discordant and ultimately incompatible halves — dutiful nerd on one side, hot mess on the other — James Rhodes’s dysfunction broke him into the proverbial million little pieces. A late-blooming British virtuoso pianist who found celebrity in part by styling himself as a sort of rock ’n’ roll bad boy of the classical world — his albums have titles like “Razor Blades, Little Pills and Big Pianos” — Rhodes never landed in jail. But reading INSTRUMENTAL: A Memoir of Madness, Medication, and Music (Bloomsbury, $27), you get the sense he wishes he could claim such dramatic levels of bottoming out. If his first love is music, his second is his own destruction. As a child he endured sexual abuse by a teacher that was horrific enough to result in long-term physical disability as well as psychological damage that led to promiscuity, substance abuse, dissociative identity disorder, suicidal ideation and self-injury. At one point, he takes off his shirt and shows his wife that he’s carved the word “toxic” into his arm with a razor blade.

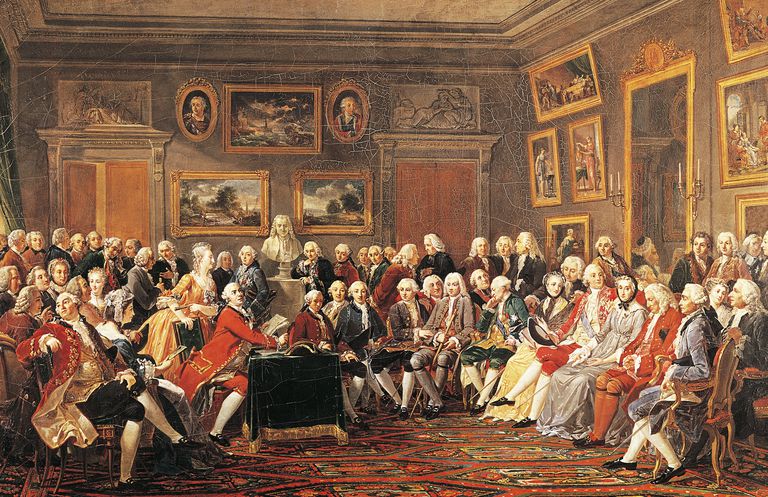

Rhodes would like us to know that he’s in good company. Musicians, even powdered-wig types like Bach and Mozart, are notorious for making train wrecks of their personal lives. As proof, Rhodes splices his own story with interstitial mini-bios of great composers, leaning heavily on the tortured nature of their genius and attendant psychosis. Schubert was “a walking, talking car crash,” Beethoven’s family was “riddled with alcoholism, domestic violence, abuse and cruelty,” and Schumann, a failed suicide, died “alone and afraid” in an asylum, but not before writing “Geister (Ghost) Variations,” a piece “so called because he said that ghosts had dictated the opening theme to him.”

Butler’s book also contains italicized interstitial sections, which she deploys to show the grueling process of learning a piece of music, making reeds or the cobbled-together life of a working musician. But while “The Skin Above My Knee” is overwritten in places (it would appear the author never met an adjective she couldn’t find a job for), it ultimately succeeds because it leaves readers knowing a thing or two about an esoteric world they probably never thought about before. “Instrumental,” for its part, hews desperately to the well-trod conventions of the well-trod genre known as Portrait of the Artist as a Young, Self-Hating Narcissist.

Quoting from “Instrumental” is tricky, since Rhodes drops an unprintable-in-a-family-newspaper epithet at least once a page. He is quite good at articulating the often intractable dimensions of shame as experienced by sexual abuse survivors. But he seems almost chemically dependent on the F-word and its innumerable iterations. His use is excessive even by the standards of the digital age, according to which “voicey” writers on the web reflexively opt for lazy vernacular as a way of branding themselves as insouciant badasses. The effect, however, is nearly always tedious and soporific, the verbal equivalent of a weary double-reed player blowing nothing but remedial long tones.

An antidote, at least of a sort, can be found in Andrew Schulman, whose earnest but affable memoir, WAKING THE SPIRIT: A Musician’s Journey Healing Body, Mind, and Soul (Picador, $25), uses the author’s own story as the first movement rather than the entire symphony. In 2009, Schulman was placed in a medically induced coma following a cascade of post-surgical complications and thought to be near death until his wife, Wendy, pressed an earbud to his head and played Bach’s “St. Matthew Passion.” Within hours, his vital signs stabilized, his life saved by “the passion of Wendy and Bach.”

Once recovered, Schulman pursues a second career as a volunteer “medical musician,” enrolling in the hospital’s music therapy program and eventually returning to the same intensive care ward where he was once a patient. If Schulman seems a little too dazzled by the notion of his own healing powers — several scenes show patients taking miraculous turns as he strums his guitar next to their beds — he redeems himself with his willingness to take on some real research and reporting. He talks with neuroscientists and psychiatrists and explores the legacy of Pythagoras, the ancient Greek mathematician and philosopher who was among the first to recognize the healing properties of music. Along the way, Schulman posits that the relationship between the pain we feel and the songs and compositions we love has its roots in a tender, transcendent form of symbiosis. “Artists who used their music to alleviate their own suffering composed some of the greatest music ever written,” Schulman writes, “which in turn has the effect of ameliorating the suffering of others.”

Not that there will ever be a cure for the suffering that music can sometimes inflict on the very musicians playing it. But, hey, it’s nice work if you can get it.

Related Posts

Kami mengalu-alukan cadangan atau komen dari pembaca. Sekiranya anda punya artikel atau pandangan balas yang berbeza, kami juga mengalu-alukan tulisan anda bagi tujuan publikasi.

Leave a Reply