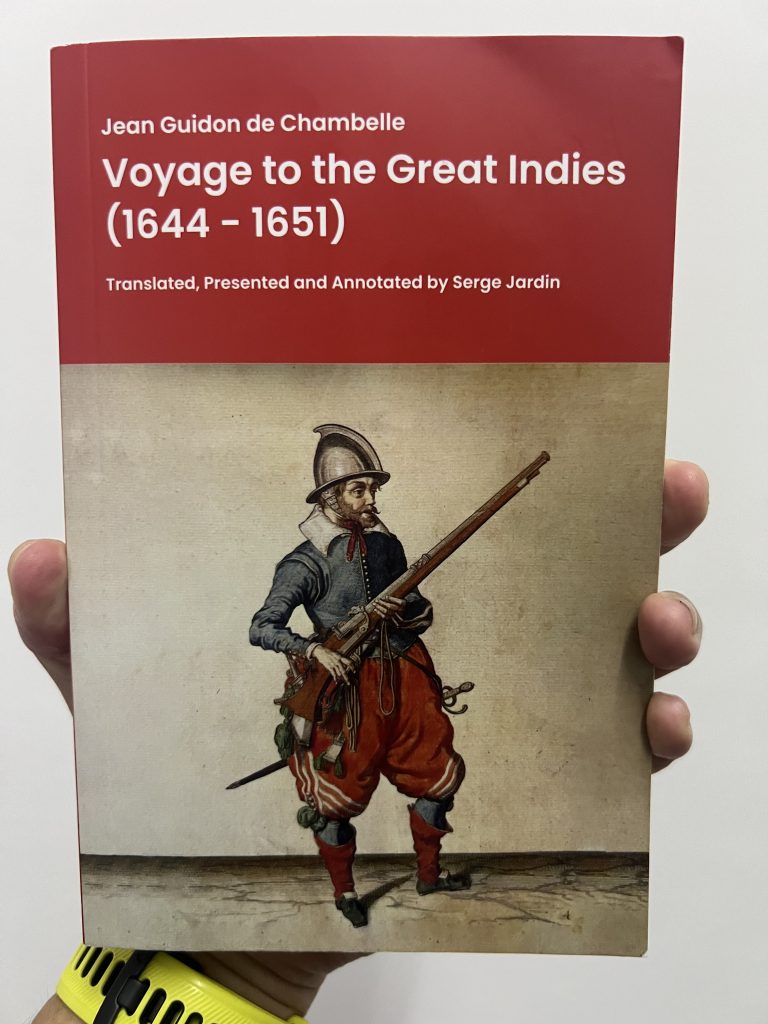

Most history reads like a collection of facts, but sometimes they can come as puzzles. The latter can be described in my latest read, a book entitled Voyage to the Great Indies by Jean Guidon de Chambelle. Jean came from a wealthy and noble family in Paris. Somehow, there was a major turning point in his life that made him sign a five-year contract as a musketeer to serve the United Dutch India Company (VOC). Like many explorers of the time, he documented his experience sailing from Amsterdam to Malacca between 1644 and 1651.

Interestingly, it seems he did not include his name on the journal, which led to the manuscript being considered an “anonymous document.” It was shelved and forgotten in the national archives. The journal later came to light when Dirk Van der Cruysse, a Belgian historian with a special interest in the VOC, resolved the case and identified the mysterious author in 2003. Even so, the journal still holds many unsolved mysteries. In 2021, Phillip Mauran, a French historian, discovered a different record in the Paris Notaries Central Minute-Record, uncovering the large network of de Chambelle’s relatives—specifically his family’s role as Parisian Protestants.

Despite this, the journal can be considered an important document that offers a better understanding of what it was like to live in Malacca in the 17th century. When we discuss a historical document, we must first ask and validate: Who wrote it? When and where was it written? Why does it exist in the first place? In this case, it was written by a Parisian who one day decided to travel thousands of miles from home to serve as a mercenary—not for gold or glory but to tell the story in a truthful manner. This is what de Chambelle reminds the reader several times at the beginning of his journal. We can consider this journal an unbiased record, not written by the Dutch, Malay, or Portuguese—parties that all had their own interests in Malacca during that time.

This journal can be separated into four sections: the voyage from Europe to Asia, the living experience in Batavia (modern-day Jakarta), life in Malacca, and the return voyage to Holland. However, don’t expect this journal to be an extensive documentation of his journey, as I felt de Chambelle’s writings do not align with the years he spent in Asia. He only recorded the most significant and interesting events that happened in Batavia and Malacca. Even so, he described places he never visited during his stay. For example, regarding the Kingdom of Acquin (Acheh), he told the story of an ambassador sent by the General to visit the Sultana Taj ul-Alam Safiatuddin Syah (the ruler of Acheh) for a peace treaty. During the visit, the ambassador broke the country’s law, which stated that no one should look at the Sultana’s face. The ambassador and his escorts were seized, forced to prostrate before an elephant, and left waiting to be executed by trampling.

I found no exaggerated facts in this book, which is a good sign. However, it is still a journal with flaws. There are some words that cannot be translated (possibly translation from Malay or Javanese words transition into French). Overall, it is an interesting read.

Part time independent writer and podcaster from Sarawak, Malaysia.